Partition representations: Difference between revisions

m (→Unification) |

(→Representation using divider locations: Non-boolean Partitioned Enclose is now common (Dyalog, April, KAP, dzaima/APL)) |

||

| (12 intermediate revisions by 3 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

[[Partition]], [[Partitioned Enclose]], | [[Partition]], [[Partitioned Enclose]], the [[Cut]] operator, and [[Cut (K)]] all allow a programmer to split a [[vector]] into differently sized pieces. The left [[argument]] to these operations defines the structure of the partition. This article discusses possible ways partitions can be represented, using [[index origin]] 0 throughout. | ||

== Definitions == | == Definitions == | ||

In this page, a '''partition''' of a [[vector]] is defined to be a [[nested]] or [[box]]ed vector containing vectors, such that the [[Raze]] (or equivalently < | In this page, a '''partition''' of a [[vector]] is defined to be a non-[[empty]] [[nested]] or [[box]]ed vector containing vectors, such that the [[Raze]] (or equivalently <syntaxhighlight lang=apl inline>{⊃⍪/⍵}</syntaxhighlight> in [[Nested array model|nested]] APLs) of the partition intolerantly [[match]]es the original vector. A partition contains all the original [[element]]s of the vector, in the same order, but at one greater [[depth]]. | ||

The vectors contained in a partition are called '''divisions''', and the boundaries between them are called '''dividers'''. Although the English word "partition" can be used for either of these, the ambiguity of using one word for three different objects could be confusing. Only boundaries between divisions are called dividers: we do not name the two outermost edges, which must exist in any partition. | The vectors contained in a partition are called '''divisions''', and the boundaries between them are called '''dividers'''. Although the English word "partition" can be used for either of these, the ambiguity of using one word for three different objects could be confusing. Only boundaries between divisions are called dividers: we do not name the two outermost edges, which must exist in any partition. | ||

| Line 13: | Line 11: | ||

== Representation using division lengths == | == Representation using division lengths == | ||

Perhaps the most obvious way to represent a partition of a vector < | Perhaps the most obvious way to represent a partition of a vector <syntaxhighlight lang=apl inline>X</syntaxhighlight> is using a vector of lengths <syntaxhighlight lang=apl inline>l</syntaxhighlight> such that <syntaxhighlight lang=apl inline>(+/l) = ≢X</syntaxhighlight>. <syntaxhighlight lang=apl inline>l</syntaxhighlight> gives the length of each division in order, that is, for a partition <syntaxhighlight lang=apl inline>P</syntaxhighlight> of <syntaxhighlight lang=apl inline>X</syntaxhighlight>, <syntaxhighlight lang=apl inline>l ≡ ≢¨P</syntaxhighlight>. Because the length vector is determined by the partition in this way, two different length vectors cannot lead to the same partition. | ||

We can obtain a partition from the division lengths by using [[Take]] twice to obtain each division. In the process, we must compute the division endpoints < | We can obtain a partition from the division lengths by using [[Take]] twice to obtain each division. In the process, we must compute the division endpoints <syntaxhighlight lang=apl inline>+\l</syntaxhighlight> using a [[Plus]] [[Scan]]. | ||

< | <syntaxhighlight lang=apl> | ||

l ← 2 0 3 3 | l ← 2 0 3 3 | ||

X ← 'abcdefgh' | X ← 'abcdefgh' | ||

| Line 23: | Line 21: | ||

│ab││cde│fgh│ | │ab││cde│fgh│ | ||

└──┴┴───┴───┘ | └──┴┴───┴───┘ | ||

</ | </syntaxhighlight> | ||

{{Works in|[[Dyalog APL]]}} | {{Works in|[[Dyalog APL]]}} | ||

The division endpoints are another way to represent partitions. The endpoints < | The division endpoints are another way to represent partitions. The endpoints <syntaxhighlight lang=apl inline>+\l</syntaxhighlight> computed above form a non-decreasing vector of non-negative integers whose last element is equal to the length of the partitioned vector. It would also be possible to use the partition starting points <syntaxhighlight lang=apl inline>+\¯1↓0,l</syntaxhighlight>; here we use only endpoints for consistency. The latter representation matches [[K]]'s [[Cut (K)|Cut]] function, which produces a complete partition exactly when the left argument contains a zero (otherwise, some initial elements are omitted). | ||

Vectors of division endpoints correspond exactly to vectors of division lengths, because the [[Windowed Reduce|windowed]] [[difference]] < | Vectors of division endpoints correspond exactly to vectors of division lengths, because the [[Windowed Reduce|windowed]] [[difference]] <syntaxhighlight lang=apl inline>¯2-/0,e</syntaxhighlight> is an exact [[inverse]] of Plus Scan which obtains division lengths <syntaxhighlight lang=apl inline>l</syntaxhighlight> from endpoints <syntaxhighlight lang=apl inline>e</syntaxhighlight>. | ||

== Representation using divider locations == | == Representation using divider locations == | ||

Existing APLs rarely define partitioning functions using properties of the resulting divisions. Instead, most partition functions use a vector of the same length as the partitioned vector to control how it is partitioned. For example, [[Partitioned Enclose]] starts a new | Existing APLs rarely define partitioning functions using properties of the resulting divisions. Instead, most partition functions use a vector of the same length as the partitioned vector to control how it is partitioned. For example, [[Partitioned Enclose]] starts a new division whenever a 1 is encountered in the [[Boolean]] left argument: | ||

< | <syntaxhighlight lang=apl> | ||

1 0 1 1 0 0 1 ⊂ 'abcdefg' | 1 0 1 1 0 0 1 ⊂ 'abcdefg' | ||

┌──┬─┬───┬─┐ | ┌──┬─┬───┬─┐ | ||

│ab│c│def│g│ | │ab│c│def│g│ | ||

└──┴─┴───┴─┘ | └──┴─┴───┴─┘ | ||

</ | </syntaxhighlight> | ||

{{Works in|[[Dyalog APL]]}} | {{Works in|[[Dyalog APL]]}} | ||

This style of partition function is slightly harder to understand and implement, but does have advantages: | This style of partition function is slightly harder to understand and implement, but does have advantages: | ||

* The left argument can sometimes be obtained directly from the right argument. For example, a | * The left argument can sometimes be obtained directly from the right argument. For example, a division might be started whenever a space is encountered. | ||

* Left arguments can be merged using arithmetic. For two [[Partitioned Enclose]] arguments < | * Left arguments can be merged using arithmetic. For two [[Partitioned Enclose]] arguments <syntaxhighlight lang=apl inline>a</syntaxhighlight> and <syntaxhighlight lang=apl inline>b</syntaxhighlight>, the [[Maximum]] <syntaxhighlight lang=apl inline>a⌈b</syntaxhighlight> gives a common [[wikipedia:Partition of a set#Refinement of partitions|refinement]] of the two corresponding partitions. | ||

A shortcoming of | A shortcoming of [[Partition]], and [[Partitioned Enclose]] in some dialects, is that they do not allow empty divisions to be produced. While the length representation makes empty divisions easy to represent, and the obvious implementation produces them with no trouble, it is less obvious how empty divisions should be represented in APL-style partitions. However, each can be modified to obtain a representation which is complete and one-to-one. [[Dyalog APL 18.0|Dyalog 18.0]] extends the domain of Partitioned Enclose from [[Boolean]] vectors to vectors of non-negative integers, so that the only further change we'll need to make is an offset of one for the first element. [[Partition]] requires more significant changes and couldn't be [[backwards compatible]] with APL definitions. | ||

=== Target indices === | === Target indices === | ||

First, we give a representation related to the one used in Partition. Recall that Partition starts a new division whenever values in its left argument increase (similar to [[Key]], except that it cares about whether values are adjacent): | First, we give a representation related to the one used in Partition. Recall that Partition starts a new division whenever values in its left argument increase (similar to [[Key]], except that it cares about whether values are adjacent): | ||

< | <syntaxhighlight lang=apl> | ||

1 1 3 3 3 3 6 ⊆ 'abcdefg' | 1 1 3 3 3 3 6 ⊆ 'abcdefg' | ||

┌──┬────┬─┐ | ┌──┬────┬─┐ | ||

│ab│cdef│g│ | │ab│cdef│g│ | ||

└──┴────┴─┘ | └──┴────┴─┘ | ||

</ | </syntaxhighlight> | ||

A more rigorous approach is to allow the left argument to specify the [[index]] of the division to which the corresponding element belongs. In order for this to produce a partition, the left argument must be a vector of non-decreasing non-negative integers (as with the division endpoint representation). Then for a left argument < | A more rigorous approach is to allow the left argument to specify the [[index]] of the division to which the corresponding element belongs. In order for this to produce a partition, the left argument must be a vector of non-decreasing non-negative integers (as with the division endpoint representation). Then for a left argument <syntaxhighlight lang=apl inline>l</syntaxhighlight> the number of divisions is <syntaxhighlight lang=apl inline>⊃⌽l</syntaxhighlight>. BQN's [[Group (BQN)|Group]] uses an extension of this representation. | ||

< | <syntaxhighlight lang=apl> | ||

1 1 3 3 3 3 6 part 'abcdefg' | 1 1 3 3 3 3 6 part 'abcdefg' | ||

┌┬──┬┬────┬┬┬─┐ | ┌┬──┬┬────┬┬┬─┐ | ||

││ab││cdef│││g│ | ││ab││cdef│││g│ | ||

└┴──┴┴────┴┴┴─┘ | └┴──┴┴────┴┴┴─┘ | ||

</ | </syntaxhighlight> | ||

Note that the non-empty divisions above are identical to those produced by Partition. The difference is that empty divisions are inserted when the index increases (including from an implicit initial index of < | Note that the non-empty divisions above are identical to those produced by Partition. The difference is that empty divisions are inserted when the index increases (including from an implicit initial index of <syntaxhighlight lang=apl inline>¯1</syntaxhighlight>) based on how many indices were skipped (since the divisions with those indices can't contain any elements). | ||

Target indices can be converted to division endpoints using [[Interval Index]], and then to division lengths with a pair-wise difference: | Target indices can be converted to division endpoints using [[Interval Index]], and then to division lengths with a pair-wise difference: | ||

< | <syntaxhighlight lang=apl> | ||

{1+⍵⍸⍳1+⊃⌽⍵}1 1 3 3 3 3 6 | {1+⍵⍸⍳1+⊃⌽⍵}1 1 3 3 3 3 6 | ||

0 2 2 6 6 6 7 | 0 2 2 6 6 6 7 | ||

¯2-/0,{1+⍵⍸⍳1+⊃⌽⍵}1 1 3 3 3 3 6 | ¯2-/0,{1+⍵⍸⍳1+⊃⌽⍵}1 1 3 3 3 3 6 | ||

0 2 0 4 0 0 1 | 0 2 0 4 0 0 1 | ||

</ | </syntaxhighlight> | ||

This conversion can be used to show that like the other two representations, target indices represent partitions bijectively. However, there is a concern regarding the final element, which is used to find the length of the division length vector above, that is, the number of divisions. If the target indices correspond exactly to the elements of the partitioned vector, then the last target index is the index of the last ''non-empty'' division. However, it is valid in a partition to include empty divisions at the end. In order to represent such divisions, we must allow an additional index after the last element of the partitioned vector. | This conversion can be used to show that like the other two representations, target indices represent partitions bijectively. However, there is a concern regarding the final element, which is used to find the length of the division length vector above, that is, the number of divisions. If the target indices correspond exactly to the elements of the partitioned vector, then the last target index is the index of the last ''non-empty'' division. However, it is valid in a partition to include empty divisions at the end. In order to represent such divisions, we must allow an additional index after the last element of the partitioned vector. | ||

| Line 76: | Line 74: | ||

The target index of an element is the same as the number of dividers which fall before it. Motivated by this fact, we might use the pair-wise differences of the target indices as another partition representation. Taking differences converts the total number of dividers before each element to the number of dividers immediately preceding it. For example, the vector below encodes the same partition as that shown in the previous section. | The target index of an element is the same as the number of dividers which fall before it. Motivated by this fact, we might use the pair-wise differences of the target indices as another partition representation. Taking differences converts the total number of dividers before each element to the number of dividers immediately preceding it. For example, the vector below encodes the same partition as that shown in the previous section. | ||

< | <syntaxhighlight lang=apl> | ||

¯2-/0,1 1 3 3 3 3 6 | ¯2-/0,1 1 3 3 3 3 6 | ||

1 0 2 0 0 0 3 | 1 0 2 0 0 0 3 | ||

| Line 83: | Line 81: | ||

││ab││cdef│││g│ | ││ab││cdef│││g│ | ||

└┴──┴┴────┴┴┴─┘ | └┴──┴┴────┴┴┴─┘ | ||

</ | </syntaxhighlight> | ||

As with the Partition-based representation, we must allow an additional element in the left argument after the end of the right argument in order to encode empty | As with the Partition-based representation, we must allow an additional element in the left argument after the end of the right argument in order to encode empty divisions after the end of the data. | ||

This definition is nearly identical to the one used in [[Partitioned Enclose | This definition is nearly identical to the one used in [[Partitioned Enclose]]. The only difference is an offset of 1 in the first element: while in Partitioned Enclose a first element of 0 indicates that no division is started, and elements before the first 1 are excluded from the final division, in the version here, a first element of 0 is like a 1 in Partitioned Enclose indicating that a division is started, while an initial 1 indicates that an empty division precedes the first non-empty division. This encoding better represents complete partitions of the right argument because every vector on non-negative integers corresponds to a partition. In Partitioned Enclose vectors beginning with 0 correspond to incomplete partitions where some initial elements are not included. However, the partitioning used in Partitioned Enclose can still be produced by [[drop]]ping the first division. | ||

== Unification == | == Unification == | ||

| Line 98: | Line 96: | ||

The partitioning mechanisms shown above can be grouped in categories in several ways. The left and right halves of the diagram each contain vectors of the same length. This is because the vectors have the same domain: on the left, a value is given for each element to be partitioned, while on the right a value is given for each division or divider. The top and bottom halves also share common properties: representations on the top specify where elements should be placed (using either dense indices giving a position for each element or sparse indices giving how many elements go in each slot) while those on the bottom specify where dividers should be placed in the same sense. | The partitioning mechanisms shown above can be grouped in categories in several ways. The left and right halves of the diagram each contain vectors of the same length. This is because the vectors have the same domain: on the left, a value is given for each element to be partitioned, while on the right a value is given for each division or divider. The top and bottom halves also share common properties: representations on the top specify where elements should be placed (using either dense indices giving a position for each element or sparse indices giving how many elements go in each slot) while those on the bottom specify where dividers should be placed in the same sense. | ||

{|class=wikitable style="margin: 1em auto 1em auto" | {|class=wikitable style="margin: 1em auto 1em auto; text-align:center" | ||

|colspan=2 rowspan=2| | |colspan=2 rowspan=2| | ||

!colspan=2| Domain | !colspan=2| Domain | ||

| Line 106: | Line 104: | ||

!rowspan=2|Positions | !rowspan=2|Positions | ||

! Elements | ! Elements | ||

| Target indices || Division lengths | | Target indices<br/>([[Partition]]) || Division lengths | ||

|- | |- | ||

! Dividers | ! Dividers | ||

| Divider counts || Division endpoints | | Divider counts<br/>([[Partitioned Enclose]]) || Division endpoints<br/>([[Cut (K)]]) | ||

|} | |} | ||

| Line 117: | Line 115: | ||

Because it interleaves elements from a vector with dividers, partitioning is closely related to the [[Mesh]] operation. In fact, a partition can be used to produce a mesh by prepending an element to each division and [[Raze]]ing: | Because it interleaves elements from a vector with dividers, partitioning is closely related to the [[Mesh]] operation. In fact, a partition can be used to produce a mesh by prepending an element to each division and [[Raze]]ing: | ||

< | <syntaxhighlight lang=apl> | ||

⎕←P | |||

┌┬──┬┬────┬┬┬─┐ | ┌┬──┬┬────┬┬┬─┐ | ||

││ab││cdef│││g│ | ││ab││cdef│││g│ | ||

| Line 124: | Line 122: | ||

⊃⍪/ 'ABCDEFG' ,¨ P | ⊃⍪/ 'ABCDEFG' ,¨ P | ||

ABabCDcdefEFGg | ABabCDcdefEFGg | ||

</ | </syntaxhighlight> | ||

The above vector is identical to the mesh of < | The above vector is identical to the mesh of <syntaxhighlight lang=apl inline>'ABCDEFG'</syntaxhighlight> with <syntaxhighlight lang=apl inline>'abcdefg'</syntaxhighlight> using mesh vector <syntaxhighlight lang=apl inline>0 0 1 1 0 0 1 1 1 1 0 0 0 1</syntaxhighlight>. | ||

A partition can also be extracted from the mesh using the [[Cut]] operator and the mesh vector. In [[J]]: | A partition can also be extracted from the mesh using the [[Cut]] operator and the mesh vector. In [[J]]: | ||

< | <syntaxhighlight lang=j> | ||

(-.0 0 1 1 0 0 1 1 1 1 0 0 0 1) <;._1 'ABabCDcdefEFGg' | (-.0 0 1 1 0 0 1 1 1 1 0 0 0 1) <;._1 'ABabCDcdefEFGg' | ||

┌┬──┬┬────┬┬┬─┐ | ┌┬──┬┬────┬┬┬─┐ | ||

││ab││cdef│││g│ | ││ab││cdef│││g│ | ||

└┴──┴┴────┴┴┴─┘ | └┴──┴┴────┴┴┴─┘ | ||

</ | </syntaxhighlight> | ||

{{Works in|[[J]]}} | {{Works in|[[J]]}} | ||

Here < | Here <syntaxhighlight lang=j inline>-.</syntaxhighlight> is [[Not]], <syntaxhighlight lang=j inline><</syntaxhighlight> is [[Box]], and <syntaxhighlight lang=j inline>;._1</syntaxhighlight> uses the Cut operator <syntaxhighlight lang=j inline>;.</syntaxhighlight> with dropped initial elements. | ||

The [[Boolean]] control vector used by Mesh serves as another way to represent partitions. Unlike the case with [[Partitioned Enclose]], a Boolean vector here is sufficient to represent any partition including those with empty divisions. This is possible because of the vector's increased length: while Partitioned Enclose uses only one Boolean for each element in the partitioned vector, the mesh vector has a 1 for each element in the partitioned vector as well as a 0 for each divider. | The [[Boolean]] control vector used by Mesh serves as another way to represent partitions. Unlike the case with [[Partitioned Enclose]], a Boolean vector here is sufficient to represent any partition including those with empty divisions. This is possible because of the vector's increased length: while Partitioned Enclose uses only one Boolean for each element in the partitioned vector, the mesh vector has a 1 for each element in the partitioned vector as well as a 0 for each divider. | ||

The mesh vector can be obtained from the other representations. In the diagram above, it contains a 1 for each horizontal line segment in the target indices graph, and a 0 for each vertical one. The directions are reversed for division endpoints. | The mesh vector can be obtained from the other representations. In the diagram above, it contains a 1 for each horizontal line segment in the target indices graph, and a 0 for each vertical one. The directions are reversed for division endpoints. | ||

< | <syntaxhighlight lang=apl> | ||

{⍵/0 1⍴⍨≢⍵},1,⍤0⍨ 0 0 0 2 1 0 ⍝ From divider counts | {⍵/0 1⍴⍨≢⍵},1,⍤0⍨ 0 0 0 2 1 0 ⍝ From divider counts | ||

1 1 1 0 0 1 0 1 1 | 1 1 1 0 0 1 0 1 1 | ||

{⍵/1 0⍴⍨≢⍵},1,⍤0⍨ 3 0 1 2 ⍝ From division lengths | {⍵/1 0⍴⍨≢⍵},1,⍤0⍨ 3 0 1 2 ⍝ From division lengths | ||

1 1 1 0 0 1 0 1 1 0 | 1 1 1 0 0 1 0 1 1 0 | ||

</ | </syntaxhighlight> | ||

In the above functions, the only difference in code is exchanging 0 and 1, and the only difference in output is an extra trailing 0 when computed from the division lengths. The mesh representation makes the partition representation duality especially clear, as the dual representation can be obtained simply by [[ | In the above functions, the only difference in code is exchanging 0 and 1, and the only difference in output is an extra trailing 0 when computed from the division lengths. The mesh representation makes the partition representation duality especially clear, as the dual representation can be obtained simply by [[Not|negating]] the mesh vector. | ||

Conversion from index-based representations is less obvious but more efficient, and also easily invertible. These representations index into either elements or dividers, but can be converted to index into the mesh vector, which combines both, by adding one for each previous index. These adjusted indices give the locations of all ones, or all zeros, in the mesh vector, depending on the initial representation. | |||

<syntaxhighlight lang=apl> | |||

⍸⍣¯1{⍵+⍳≢⍵} 0 0 0 2 3 3 ⍝ From target indices | |||

1 1 1 0 0 1 0 1 1 | |||

~⍸⍣¯1{⍵+⍳≢⍵} 3 3 4 6 ⍝ From division endpoints | |||

1 1 1 0 0 1 0 1 1 0 | |||

</syntaxhighlight> | |||

The adjusted target indices and division endpoints combine with the mesh vector and its negation to give a set of four representations that parallel the four partition representations. Instead of using lists of natural numbers, and nondecreasing lists of natural numbers, these use lists of booleans, and strictly increasing lists of natural numbers. They may be considered a representation of sets rather than multisets of natural numbers. | |||

[[Category:Essays]] | |||

Latest revision as of 16:19, 30 December 2023

Partition, Partitioned Enclose, the Cut operator, and Cut (K) all allow a programmer to split a vector into differently sized pieces. The left argument to these operations defines the structure of the partition. This article discusses possible ways partitions can be represented, using index origin 0 throughout.

Definitions

In this page, a partition of a vector is defined to be a non-empty nested or boxed vector containing vectors, such that the Raze (or equivalently {⊃⍪/⍵} in nested APLs) of the partition intolerantly matches the original vector. A partition contains all the original elements of the vector, in the same order, but at one greater depth.

The vectors contained in a partition are called divisions, and the boundaries between them are called dividers. Although the English word "partition" can be used for either of these, the ambiguity of using one word for three different objects could be confusing. Only boundaries between divisions are called dividers: we do not name the two outermost edges, which must exist in any partition.

We consider two partitions of a vector to be identical if they match, ignoring prototypes. Since partitions of the same vector contain the same data, and in the same order, they match when they have identical structure. The partition representations discussed below are ways of encoding structure; a desirable quality of a partition representation is that two partitions match exactly when their representations match.

Representation using division lengths

Perhaps the most obvious way to represent a partition of a vector X is using a vector of lengths l such that (+/l) = ≢X. l gives the length of each division in order, that is, for a partition P of X, l ≡ ≢¨P. Because the length vector is determined by the partition in this way, two different length vectors cannot lead to the same partition.

We can obtain a partition from the division lengths by using Take twice to obtain each division. In the process, we must compute the division endpoints +\l using a Plus Scan.

l ← 2 0 3 3

X ← 'abcdefgh'

(-l) ↑¨ (+\l) ↑¨ ⊂X

┌──┬┬───┬───┐

│ab││cde│fgh│

└──┴┴───┴───┘

The division endpoints are another way to represent partitions. The endpoints +\l computed above form a non-decreasing vector of non-negative integers whose last element is equal to the length of the partitioned vector. It would also be possible to use the partition starting points +\¯1↓0,l; here we use only endpoints for consistency. The latter representation matches K's Cut function, which produces a complete partition exactly when the left argument contains a zero (otherwise, some initial elements are omitted).

Vectors of division endpoints correspond exactly to vectors of division lengths, because the windowed difference ¯2-/0,e is an exact inverse of Plus Scan which obtains division lengths l from endpoints e.

Representation using divider locations

Existing APLs rarely define partitioning functions using properties of the resulting divisions. Instead, most partition functions use a vector of the same length as the partitioned vector to control how it is partitioned. For example, Partitioned Enclose starts a new division whenever a 1 is encountered in the Boolean left argument:

1 0 1 1 0 0 1 ⊂ 'abcdefg' ┌──┬─┬───┬─┐ │ab│c│def│g│ └──┴─┴───┴─┘

This style of partition function is slightly harder to understand and implement, but does have advantages:

- The left argument can sometimes be obtained directly from the right argument. For example, a division might be started whenever a space is encountered.

- Left arguments can be merged using arithmetic. For two Partitioned Enclose arguments

aandb, the Maximuma⌈bgives a common refinement of the two corresponding partitions.

A shortcoming of Partition, and Partitioned Enclose in some dialects, is that they do not allow empty divisions to be produced. While the length representation makes empty divisions easy to represent, and the obvious implementation produces them with no trouble, it is less obvious how empty divisions should be represented in APL-style partitions. However, each can be modified to obtain a representation which is complete and one-to-one. Dyalog 18.0 extends the domain of Partitioned Enclose from Boolean vectors to vectors of non-negative integers, so that the only further change we'll need to make is an offset of one for the first element. Partition requires more significant changes and couldn't be backwards compatible with APL definitions.

Target indices

First, we give a representation related to the one used in Partition. Recall that Partition starts a new division whenever values in its left argument increase (similar to Key, except that it cares about whether values are adjacent):

1 1 3 3 3 3 6 ⊆ 'abcdefg' ┌──┬────┬─┐ │ab│cdef│g│ └──┴────┴─┘

A more rigorous approach is to allow the left argument to specify the index of the division to which the corresponding element belongs. In order for this to produce a partition, the left argument must be a vector of non-decreasing non-negative integers (as with the division endpoint representation). Then for a left argument l the number of divisions is ⊃⌽l. BQN's Group uses an extension of this representation.

1 1 3 3 3 3 6 part 'abcdefg' ┌┬──┬┬────┬┬┬─┐ ││ab││cdef│││g│ └┴──┴┴────┴┴┴─┘

Note that the non-empty divisions above are identical to those produced by Partition. The difference is that empty divisions are inserted when the index increases (including from an implicit initial index of ¯1) based on how many indices were skipped (since the divisions with those indices can't contain any elements).

Target indices can be converted to division endpoints using Interval Index, and then to division lengths with a pair-wise difference:

{1+⍵⍸⍳1+⊃⌽⍵}1 1 3 3 3 3 6

0 2 2 6 6 6 7

¯2-/0,{1+⍵⍸⍳1+⊃⌽⍵}1 1 3 3 3 3 6

0 2 0 4 0 0 1

This conversion can be used to show that like the other two representations, target indices represent partitions bijectively. However, there is a concern regarding the final element, which is used to find the length of the division length vector above, that is, the number of divisions. If the target indices correspond exactly to the elements of the partitioned vector, then the last target index is the index of the last non-empty division. However, it is valid in a partition to include empty divisions at the end. In order to represent such divisions, we must allow an additional index after the last element of the partitioned vector.

Divider counts

The target index of an element is the same as the number of dividers which fall before it. Motivated by this fact, we might use the pair-wise differences of the target indices as another partition representation. Taking differences converts the total number of dividers before each element to the number of dividers immediately preceding it. For example, the vector below encodes the same partition as that shown in the previous section.

¯2-/0,1 1 3 3 3 3 6

1 0 2 0 0 0 3

1 0 2 0 0 0 3 penc 'abcdefg'

┌┬──┬┬────┬┬┬─┐

││ab││cdef│││g│

└┴──┴┴────┴┴┴─┘

As with the Partition-based representation, we must allow an additional element in the left argument after the end of the right argument in order to encode empty divisions after the end of the data.

This definition is nearly identical to the one used in Partitioned Enclose. The only difference is an offset of 1 in the first element: while in Partitioned Enclose a first element of 0 indicates that no division is started, and elements before the first 1 are excluded from the final division, in the version here, a first element of 0 is like a 1 in Partitioned Enclose indicating that a division is started, while an initial 1 indicates that an empty division precedes the first non-empty division. This encoding better represents complete partitions of the right argument because every vector on non-negative integers corresponds to a partition. In Partitioned Enclose vectors beginning with 0 correspond to incomplete partitions where some initial elements are not included. However, the partitioning used in Partitioned Enclose can still be produced by dropping the first division.

Unification

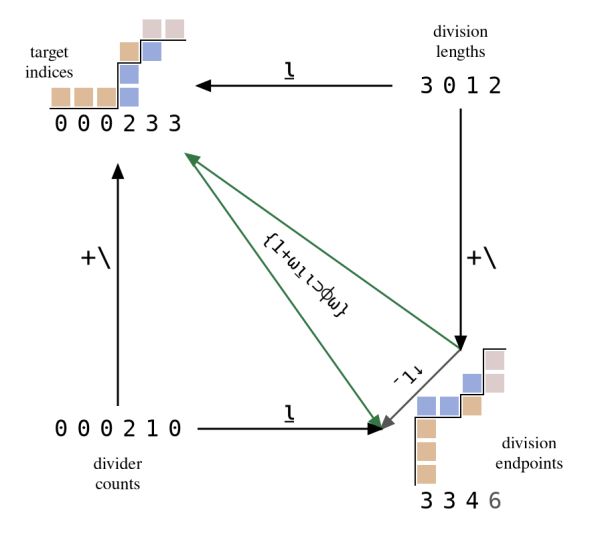

The division-based and divider-based representations are dual to one another: counting the number of elements with no divisions in between and the number of dividers with no elements in between are symmetric concepts. We can convert between them using the Indices primitive and its inverse. The following diagram shows the relationships between the four representations. Note the symmetry in the graphs for target indices and division endpoints: the graphs are essentially transposes of one another. The Interval Index function can be used to convert between these two representations directly.

The relationship between the two kinds of partition representations is in principle symmetric, but we must introduce an asymmetry in order to handle the final division or divider (for infinite arrays there would be no need). There can always be elements past the last divider, or dividers beyond the last element. But dividers are placed between elements, and elements between dividers: effectively, they are offset by a half-index. Going halfway around the circle above must either accumulate or remove a half index; going all the way around by using the same transformation twice would add or drop an entire index. We must insert a step at some point in the cycle to account for this index, but it can be placed in any part of the diagram—there is no reason it must be in the lower-right corner as above.

The partitioning mechanisms shown above can be grouped in categories in several ways. The left and right halves of the diagram each contain vectors of the same length. This is because the vectors have the same domain: on the left, a value is given for each element to be partitioned, while on the right a value is given for each division or divider. The top and bottom halves also share common properties: representations on the top specify where elements should be placed (using either dense indices giving a position for each element or sparse indices giving how many elements go in each slot) while those on the bottom specify where dividers should be placed in the same sense.

| Domain | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Dividers | Divisions | ||

| Positions | Elements | Target indices (Partition) |

Division lengths |

| Dividers | Divider counts (Partitioned Enclose) |

Division endpoints (Cut (K)) | |

Another grouping appears when considering how values are indicated. The divider counts and division lengths are counts, while the target indices and division endpoints are indices. This difference is reflected in the domains of these representations: while counts are allowed to be any vector of non-negative integers, indices must additionally be non-decreasing.

Mesh representation

Because it interleaves elements from a vector with dividers, partitioning is closely related to the Mesh operation. In fact, a partition can be used to produce a mesh by prepending an element to each division and Razeing:

⎕←P

┌┬──┬┬────┬┬┬─┐

││ab││cdef│││g│

└┴──┴┴────┴┴┴─┘

⊃⍪/ 'ABCDEFG' ,¨ P

ABabCDcdefEFGg

The above vector is identical to the mesh of 'ABCDEFG' with 'abcdefg' using mesh vector 0 0 1 1 0 0 1 1 1 1 0 0 0 1.

A partition can also be extracted from the mesh using the Cut operator and the mesh vector. In J:

(-.0 0 1 1 0 0 1 1 1 1 0 0 0 1) <;._1 'ABabCDcdefEFGg' ┌┬──┬┬────┬┬┬─┐ ││ab││cdef│││g│ └┴──┴┴────┴┴┴─┘

Here -. is Not, < is Box, and ;._1 uses the Cut operator ;. with dropped initial elements.

The Boolean control vector used by Mesh serves as another way to represent partitions. Unlike the case with Partitioned Enclose, a Boolean vector here is sufficient to represent any partition including those with empty divisions. This is possible because of the vector's increased length: while Partitioned Enclose uses only one Boolean for each element in the partitioned vector, the mesh vector has a 1 for each element in the partitioned vector as well as a 0 for each divider.

The mesh vector can be obtained from the other representations. In the diagram above, it contains a 1 for each horizontal line segment in the target indices graph, and a 0 for each vertical one. The directions are reversed for division endpoints.

{⍵/0 1⍴⍨≢⍵},1,⍤0⍨ 0 0 0 2 1 0 ⍝ From divider counts

1 1 1 0 0 1 0 1 1

{⍵/1 0⍴⍨≢⍵},1,⍤0⍨ 3 0 1 2 ⍝ From division lengths

1 1 1 0 0 1 0 1 1 0

In the above functions, the only difference in code is exchanging 0 and 1, and the only difference in output is an extra trailing 0 when computed from the division lengths. The mesh representation makes the partition representation duality especially clear, as the dual representation can be obtained simply by negating the mesh vector.

Conversion from index-based representations is less obvious but more efficient, and also easily invertible. These representations index into either elements or dividers, but can be converted to index into the mesh vector, which combines both, by adding one for each previous index. These adjusted indices give the locations of all ones, or all zeros, in the mesh vector, depending on the initial representation.

⍸⍣¯1{⍵+⍳≢⍵} 0 0 0 2 3 3 ⍝ From target indices

1 1 1 0 0 1 0 1 1

~⍸⍣¯1{⍵+⍳≢⍵} 3 3 4 6 ⍝ From division endpoints

1 1 1 0 0 1 0 1 1 0

The adjusted target indices and division endpoints combine with the mesh vector and its negation to give a set of four representations that parallel the four partition representations. Instead of using lists of natural numbers, and nondecreasing lists of natural numbers, these use lists of booleans, and strictly increasing lists of natural numbers. They may be considered a representation of sets rather than multisets of natural numbers.